010-80850896;13001093985

010-80850896;13001093985

2017-03-29 21:00:08.842 GMT

By Bloomberg News (Bloomberg Businessweek)

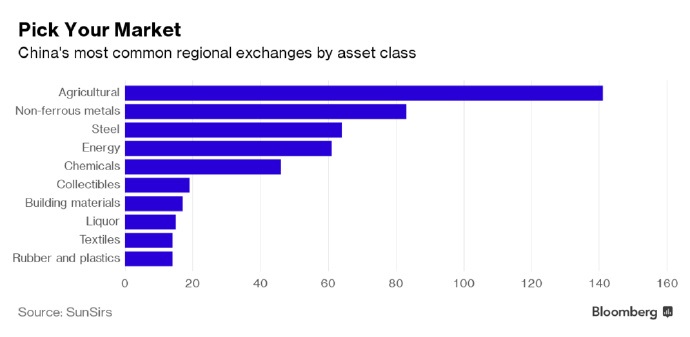

-- Chances are, if you can buy itor sell it, China has an exchange for it. The latest example?The China Donkey Exchange. It’s one of more than 1,000 tradingvenues that now dot Asia’s largest economy, up from 300 in 2011,according to SunSirs, a provider of data and research on Chinesecommodity markets. The country has everything from the national stockexchanges in Shanghai and Shenzhen to small operations thatconsist of little more than software for matching buyers andsellers. But regional trading venues are becoming ever-biggerplayers. Helping determine prices for agricultural products,metals, and chemicals, they now cover 32 of China’s 34provincial-level regions. An orchid exchange began operating inYunnan province in September, and a market for small-companyshares opened in Ningbo in May.

Properly run exchanges “are beneficial to the developmentof China’s markets,” says Hao Hong, chief strategist at BocomInternational Holdings Co. in Hong Kong. But the rapid increaseand sheer number of trading platforms have also raised concernsabout patchy oversight. “Many of the exchanges started as aplace of hedging but evolved into a place of speculation, whichin excess brings no obvious benefits to the real economy,” Hongadds.

The donkey exchange was born for much the same reason hogand soybean futures are traded around the world. Donkeys inChina are not just beasts of burden, but an agriculturalcommodity. A traditional treatment for anemia known as e’jiao ismade from boiled donkey skin. Demand for e’jiao, which can bepurchased as a cooked gelatin, has surged in the past decade asmillions have joined China’s middle class. Donkey prices have quadrupled over the same period—to about8,000 yuan ($1,160) a head—in part because breeders have failedto replenish their herds. Donkeys are hard to breed quickly; theanimals have long pregnancies, lasting up to 14 months. The demand from China is being felt internationally. Niger,the BBC has reported, has banned the export of donkeys topreserve the animal there; Burkina Faso has banned the export oftheir skins. In some places where donkeys are used in farmingand other work, the trade “has inflated prices for donkeys somuch that families that depend on them can’t replace theirdonkeys,” says Mike Baker, chief executive officer of the DonkeySanctuary, a U.K. charity. In China, e’jiao companies have trouble finding enoughskins to keep their factories busy. Dong-E-E-Jiao Co., a state-owned producer, launched the exchange in December to “promotethe industry of donkey breeding and raise nationwideproduction,” says Liu Guangyuan, who oversees the project. The marketplace, based in a rural part of Shandongprovince, handles transactions over the telephone. A farmer cancall to say he wants to sell a group of donkeys, and theexchange will send a so-called runner—it employs more than100—to confirm the animals exist and meet quality standards. Itwill help find a price both seller and buyer agree on andarrange shipping after a deal is struck. More than 370 million yuan’s worth of donkeys have changedhands on the exchange since it opened. Dong-E-E-Jiao says thatfigure will probably reach 1.5 billion yuan by yearend, and itplans to start web- and app-based trading in April. Liu saysDong-E-E-Jiao doesn’t trade on the market for its own account,because it doesn’t buy live donkeys. Instead, it buys skinsafter the animals have been slaughtered. The proliferation of Chinese exchanges has fueled concernsin Beijing that local authorities aren’t equipped to supervisethem properly. In January a group of national ministriesresponsible for monitoring regional markets said in a statementthat some platforms had been engaged in illegal activity, addingthat venues for stamps, coins, and collectible cards had facedmarket manipulation allegations. It didn’t disclose names. One recent episode illustrates the risks. In 2015 policealleged that the owner of China Gold & Silver Trade Center, acommodities exchange in the northern autonomous region of InnerMongolia, had fled with users’ funds. China Gold & Silver’swebsite is now inaccessible; calls to its phone number, listedin filings with the State Administration for Industry andCommerce, didn’t go through; and it didn’t respond to an emailseeking comment. An official at the local police department inChifeng, which posted the allegations on its official Weiboaccount, said by phone that the case had been transferred toBeijing, without providing further details. Problematic exchanges “siphon funds from proper markets toparticipate in speculation, undermine order in financialmarkets, and should be cleared promptly,” says Wang Deyi, a lawyer at Beijing Xunzhen Law Firm who’s represented investorsin cases against regional exchanges. Still, there are plenty of success stories among the newmarkets. One of the most notable is the China Stainless SteelExchange, which opened in 2006 and now has all the hallmarks ofa major futures market: centralized trading, standardizedcontracts, warehousing, and third-party custodians. Theexchange, which operates almost continuously on weekdays, rivalsthe nationally regulated Shanghai Futures Exchange as a providerof benchmark pricing for nickel. While China stands out for the sheer number of itsexchanges, many of the venues were “spawned from needs in thereal economy,” says Man Rongrong, a senior analyst at SunSirs inShandong. The challenge is to keep them grounded there. The bottom line: The China Donkey Exchange is one of morethan 700 market platforms that have sprouted in the countrysince 2011.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-03-29/china-has-exchange-traded-donkeys

扫一扫了解更多

扫一扫了解更多 扫一扫了解更多

扫一扫了解更多COPYRIGHT©2022ALL RIHGTS RESERVED 北京寻真律师事务所 版权所有 京ICP备2022011643号